-

Overview

Painterly Expressionists: E. Newmann, J. Connell, Sam Scott, R. Hogan, Z. Rieke

7 October - 25 November, 2023

ENDURING MASTERS FROM SANTA FE’S ARTISTIC RENAISSANCE OF THE 70S & 80S

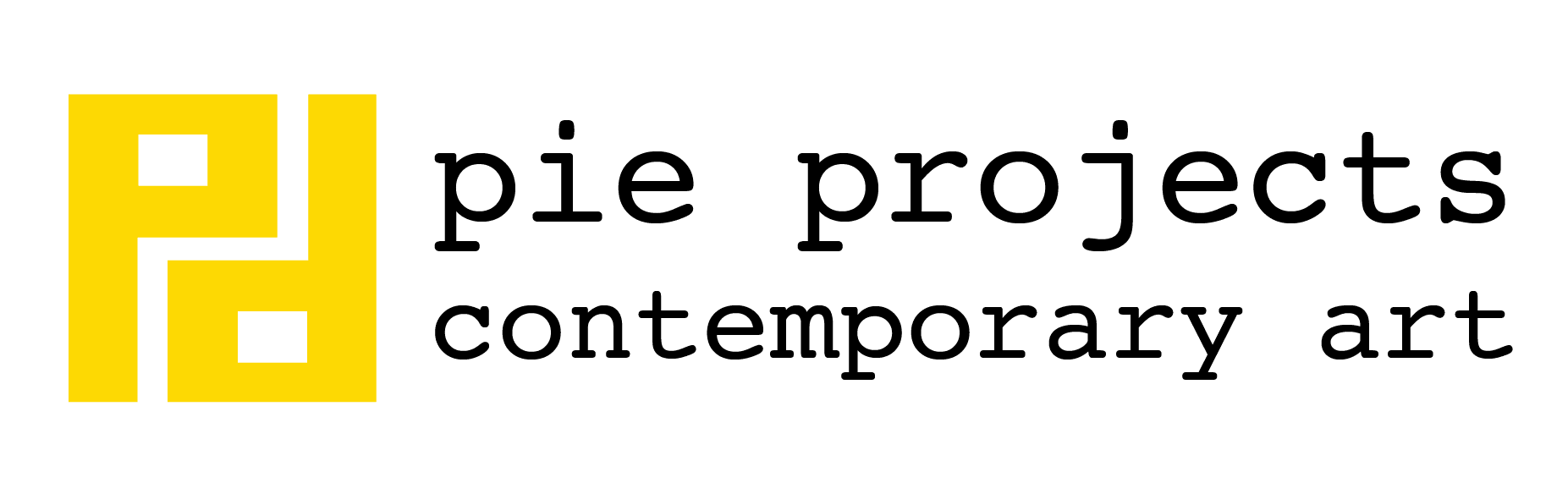

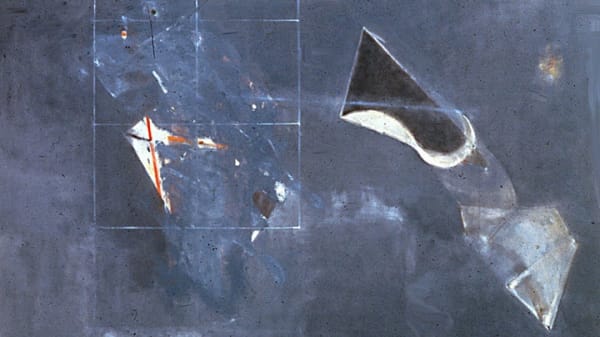

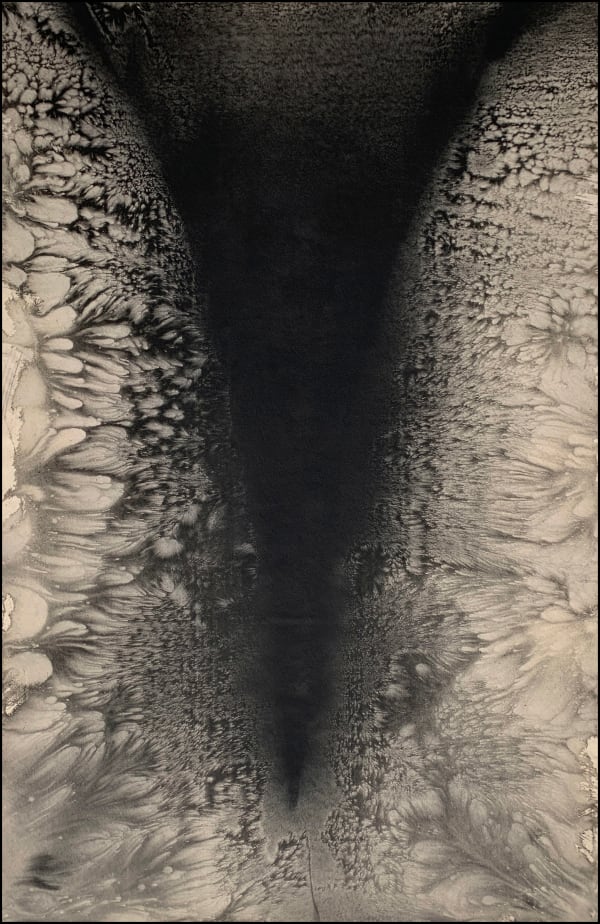

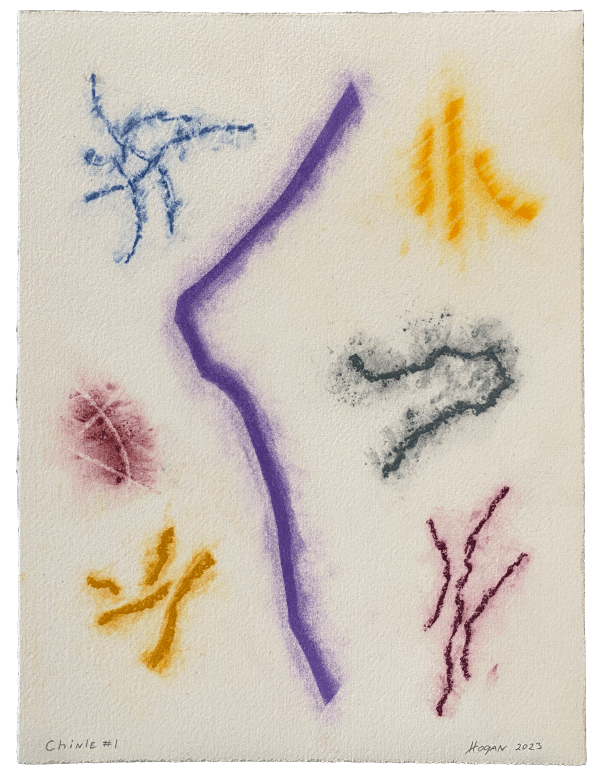

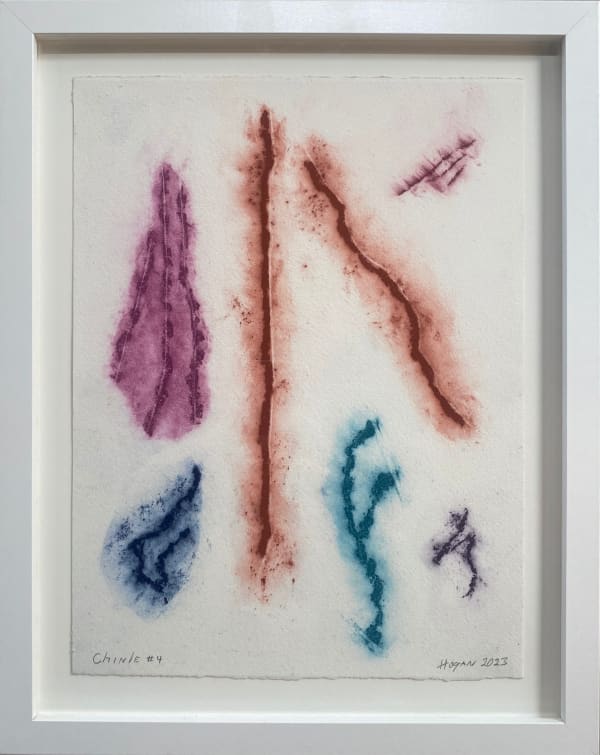

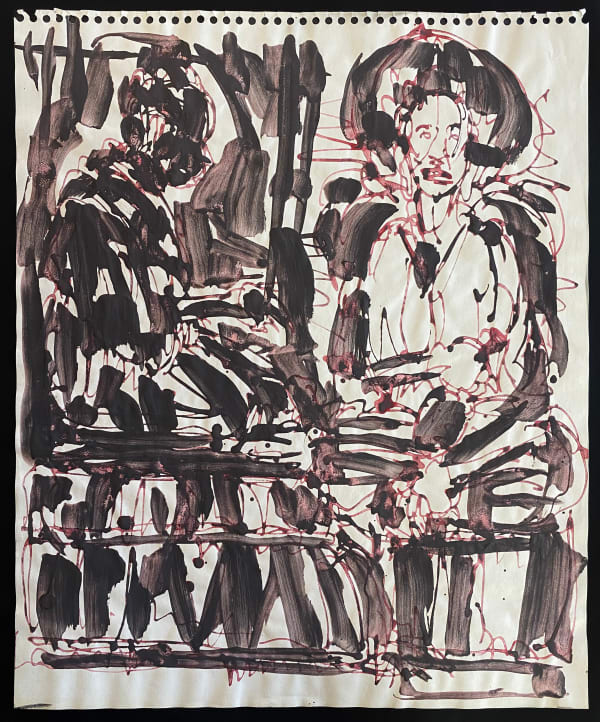

In recognition of the Museum of Art’s new Vladem Contemporary, Pie Projects Contemporary Art is pleased to present work by five artists who led the initial advance of contemporary art in New Mexico. Eugene Newmann, John Connell, Sam Scott, Richard Hogan, and Zachariah Rieke were there at the beginning and helped kick-start Santa Fe’s artistic renaissance in the 1970s & 80s.Except for John Connell, who died in 2009, all continue to produce as accomplished masters. What links these artists is not just a moment of time in a particular place, but a shared attitude toward the physicality of painting – how its rough material substance can be sublimated to higher expression.Their raw approach did not ingratiate itself to lovers of golden aspens and honey-toned adobes with red chile ristras and turquoise trim, the imagery most expected to see in Santa Fe’s galleries at the time. They were deemed outlaws of art, and their works continue to present challenges. Striving to keep faith with the history of art, they paint for the museums, not the marketplace. Their aim is to create objects of integrity, paintings that are essentially metaphoric projections of what it means to be an incarnate human being, a physical body infused with spiritual aspiration and unrest.“I admire painting that is rooted in the world,” Eugene Newmann stated in 1975. It was his way of noting that, despite the abstract appearance of his canvases, his concerns are worldly. Born in 1936 in Bratislava, Slovakia, Newmann was brought to Baranquilla, Colombia as a child when his parents fled the Holocaust. He was sent to New York for his education and then attended the University of Chicago, where he studied mathematics and later took up art. He and his wife Dana arrived in Santa Fe in 1972. Melding figuration with abstraction, Newmann’s surfaces are rich with evidence of doubt, disputation and revision as the work progresses. Hints of geometry imply an analytic search for order, and occasional nods to the Old Masters – Vermeer, Titian, Rubens, Manet – join themes of human frailty and perplexity, all of which Newmann ponders with an eloquence of oil paint reminiscent of Rembrandt.John Connell (1940 – 2009) arrived in Santa Fe in 1968 from San Francisco, where he had been part of the Beat poetry scene. Using a painterly approach to making sculpture, Connell dipped newspapers in tar or plaster to build up keenly observed birds and humans, often in Buddhist-inspired settings. In 1980 he and Gene Newmann collaborated on The Raft Project, an installation of Connell’s figures adrift on a make-shift raft beneath the fateful sky-charts of Newmann’s vast paintings. Although they were meant to be ephemeral, Connell sometimes cast his Arte Povera sculptures in bronze, like baby shoes preserved as trophies of lost innocence. Grinding his own earth pigments, he also made exquisite drawings and large brushy works on paper.In 1979 William Peterson described Sam Scott’s paintings as “a manifestation of the earthly urge to celebrate sensation in colored matter which is all spirit.” Born in 1940 in Chicago, Sam Scott came to New Mexico in 1969 after studying with Grace Hartigan, Philip Guston, and Clyfford Still in Baltimore. Already a world traveler with firsthand knowledge of Native American spirituality, in Santa Fe and Tucson he honed his mythopoetic sensibility. “Painting is an act of reparation,” he has said. Hoping to repair humanity’s breech with nature, he continues to produce lushly colored abstractions and works with a fugitive figuration and brushstrokes that reference the essential intermingling of creation and destruction in all natural processes. His work largely shifts between two modes, sometimes condensing to a single monolithic mass, representative of the embattled and enduring heroic ego, and at other times opening into fields of dispersed linear activity, invoking landscape and the diverse energies of the blooming and buzzing world.Richard Hogan, born in 1941 in Youngstown, Ohio, came to New Mexico as a child when his parents settled in Albuquerque’s Southeast Heights. He was immediately struck by the vast open space of New Mexico, and space would become a major factor in his painting. In 1979 he shifted from a representational style with isolated figures influenced by Francis Bacon to a fully abstract approach restricted to inscribing a few isolated lines. Addressed to the vertical viewer standing in front of the canvas, these lines articulate a bodily apprehension of space as a visual field, which opens like cinema before our eyes. Over time the lines grew in thickness and color and were variously rubbed out and restruck. In the 1990s and early 2000s, the paintings became spare and restrained, their marks often evoking paleolithic cave etchings. Marks also thickened into shapes that separated into matt patches with honed edges, like Celtic monoliths. Later works darkened as their fields turned foggy behind a few emphatic linear shapes and their rubbed-out colors faded into delicate Rococo traceries.Zachariah Rieke, born in 1943, was raised on a Kansas farm where the weathered and rusting remnants of Depression-era failure were a common reminder of human striving against the indifferent forces of nature. Schooled in late-phase Abstract Expressionism, by the time he and his wife Gail arrived in New Mexico in 1970, he had evolved a unique form of action painting that entailed close collaboration with natural processes. Using earth pigments and employing a variety of techniques to replicate the effects of weathering and erosion, he invoked the natural cycles of aging and endurance. He also sought the natural spontaneity of Zen calligraphic brushwork in large black-pigment paintings, and he has recently turned to broad layered washes and stains of poured pigment in lush colors. -

-

Works

E. Newmann, J. Connell, Sam Scott, R. Hogan, Z. Rieke, 7 October - 25 November 2023

Find out more about upcoming exhibitions.

* denotes required fields

We will process the personal data you have supplied in accordance with our privacy policy (available on request). You can unsubscribe or change your preferences at any time by clicking the link in our emails.